Topics

On This Page

There are many barriers to access in education at all levels. These barriers range from cost of education and textbooks to geographical distance or transportation challenges, lifestyle, and work. Where education is delivered through technology—such as the Internet and computers or mobile devices—access to networks and affordability of devices can constitute barriers. Within the learning environment itself, rules of copyright can limit teaching and learning practices, making it difficult for faculty and students to adapt and contextualize purchased commercial learning resources, particularly textbooks.

Another form of restriction of access, especially in higher education, is the prerequisite education and grades required in many institutions, making it onerous for individuals to start a university education in spite of their potentially many years of experience and learning in other, non-formal contexts.

There have been many efforts over the years to rethink these barriers and challenge their role in limiting access to education. In this unit we will explore some dimensions of open educational practices including the growth of open educational resources. Discourses in education continue to unfold and expand the idea of open education, defying any one effort to produce a final definition. It is a moving and emerging target, and with great implications for educators in all settings, levels, disciplines and sectors.

Resources

K–12 Online Learning

Cavanaugh, C. S., Barbour, M. K., & Clark, T. (2009). Research and practice in K–12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i1.607

Benefits of OER for K–12 Learning

Blomgren, C. & Roberts, V. (2017). Benefits of OER for K–12 learning [Podcast]. Athabasca University. http://bolt.athabascau.ca/index.php/podcast/benefits-of-oer-for-k-12-learning/

Open Educational Practices

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Open Pedagogies

Hegarty, B. (2015, July–August). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 3-13. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/Ed_Tech_Hegarty_2015_article_attributes_of_open_pedagogy.pdf

From OER to OEP

Ehlers, U. D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1-10. http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64/46

Defining Open in OER

Wiley, D. (n.d.). Defining the “open” in open content and open educational resources. http://opencontent.org/definition/

Recognition of Informal Learning, PLAR

Harris, J., & Wihak, C. (2018). The recognition of non-formal education in higher education: Where are we now, and are we learning from experience? International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 33(1). http://ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1058

Course Notes

K–12 Online Learning

Online learning is gaining increasing attention in schools systems around the world, in the form of both fully online schools and traditional schools using online courses provided by others such as universities, school districts or departments of education to increase access for students. Online learning opens up access to education where limitations exist for a number of reasons, such as living in a remote area, confinement to a home or health institution, or simply unavailability of required or desired courses at one’s regular school, among others as described by Cavanaugh, Barbour and Clark (2009).

In Canada, online learning is available in a number of ways for school-age students, including individual schools or districts, specially mandated open schools or education ministry departments, adult learning and upgrading schools or programs, and some universities providing university preparation courses for adults.

In their review of research in online schooling, the authors cite both benefits and challenges, such as the expense of developing such courses and programs, digital access, and accreditation or credibility of open schools where they do exist. Recommendations out of the research on available literature includes the need for more empirical research, success factors for students, bridging the divide between online and face-to-face students, and gaining a better understanding of student experiences.

Given that online learning is more prevalent in higher education, much of the research noted by the authors is at a more advanced level, and more thoroughly investigated, in higher education and in many cases researchers and practitioners may look to higher education research and practices, and see how they may adapt to other educational settings. Of course a major difference is in the extent of prescribed curriculum, the mandatory nature of most schooling, and the maturity level of students apart from adult upgrading to meet high school requirements.

Important aspects of teaching and learning online for schools is well explored through digital literacies, as discuss elsewhere in this course.

Cavanaugh, C. S., Barbour, M. K., & Clark, T. (2009). Research and practice in K–12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i1.607

Benefits of OER for K–12 Learning

OER, or open educational resources, have not gained as much attention in the K–12 system as they have in other settings. Within higher education, OER gained attention initially mainly as a way to reduce costs of education. While in higher education the cost of textbooks is felt mainly by students, in K–12 textbooks are the responsibility of the school districts and the costs are somewhat removed from students. For those who have explored this issue further in K–12, however, the argument for OER, especially open textbooks, beyond costs has been their capacity to be edited and customized by teachers following the benefits of open (Creative Commons) licensing as well as the ability to follow the “five R’s” of open educational resources, i.e. the ability to reuse, revise, remix, redistribute and retain open educational resources such as textbooks. As compared with the rigidly copyrighted textbooks obtained through the traditional textbook industry, open textbooks allow for much more flexible uses of the textbook by teachers and even by students.

In this podcast, speaker Royce Kimmons nots that while, as noted above, cost isn’t a big factor in K–12 educational licensing choices, “there are also pedagogical potentials and professional potentials. So, in relation to pedagogy, teachers can use open educational resources and adopt other practices of openness to help increase their ability to differentiate for individual student needs. So this is a huge issue right now in education, and trying to make sure that we’re meeting the needs of each of our diverse students.” Because of the open license and the ability to access and edit the source material, much more localization and customization is enabled as well as the ability to teach in multiple ways. Sarah Weston further places OER in the context of educational technologies: “So there have been some amazing advances in ed-tech and delivery over the last seven years, and we’ve been able to witness them, it’s been awesome. But this movement and this growth and all these digital resources, it’s ironic. It has led to the development of some of the most engaging and thoughtful and beautifully-designed lessons, but they’re static. So we have static curriculum out there that’s been developed in this surge in ed tech and learning objects.” OER comes into play at this point, as it can provide the freedom to “… take that content, and you can edit and revise it to meet the needs of your students, which is a basic tenet of teaching. This is what we do. And we have digital content that’s not OER, it’s copyrighted; you can’t do with it what you want to do as a teacher, but OER allows you to do with the curriculum what you are always doing. And that flexibility is one of its biggest strengths.”

Another area to think about, not referenced in this interview, is the extent to which students themselves can contribute to OER or open textbooks, such as their own media that they have developed for a course, cast studies examples, and so forth, increasing their own sense of ownership of learning and the resources used.

Blomgren, C. & Roberts, V. (2017). Benefits of OER for K–12 learning [Podcast]. Athabasca University. http://bolt.athabascau.ca/index.php/podcast/benefits-of-oer-for-k-12-learning/

Open Educational Practices

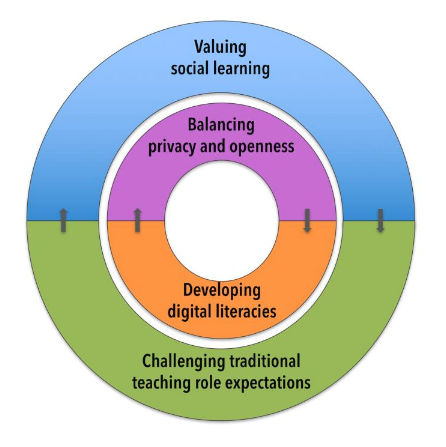

Cronin (2017) explores how open educational practices (OEP) play out among university educators. Narratives with similar features can be found in K–12 education as well as some workplace education and training settings. As Cronin notes, openness in education can take a variety of forms including open admission to formal education, open as free of cost as well as onerous copyright restrictions, open educational resources (OER) which is educational content and tools that can be used and adapted for other purposes without cost due to open licensing, and open educational practices which in this setting focuses on different ways of teaching and learning, sharing the control of learning experiences with learners. Cronin finds that “It is impossible to draw a clear boundary between educators who do and do not use OEP. Instead there is a continuum of practices and values ranging from ‘closed’ to open. A complex picture emerges of a broad range of educators: some open (in one or more ways), some not; some moving towards openness (in one or more ways), some not; but all thinking deeply about their digital and pedagogical decisions (2017, p. 21). Among the range of practices found by Cronin were such aspects as “open digital identity; using social media for personal and professional use, including teaching; using both a VLE and open tools; using and reusing OER; valuing both privacy and openness; and accepting some porosity across personal-professional and staff-student boundaries” (p. 21). These aspects illustrate the broad ranges of practices that can be seen as part of openness in education; “being open,” an orientation toward a culture of sharing and personal openness appears to lie at the roots of open educational practices; and “teach openly,” i.e. exposing the inner processes of a formal learning event (course) more broadly outside the confines of password-protected learning management systems toward openly accessible social media. In exploring OEP among educations, Cronin identified four dimensions that became evident, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Four Dimensions Shared by Educators Using OEP

Figure 1. Four Dimensions Shared by Educators Using OEP. Note. From “Openness and Praxis” by C. Cronin, 2017. (https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096)

These dimensions have the potential to influence change in the way teaching takes place, as well as in the activities learners need to participate in and take responsibility for.

Open Pedagogies

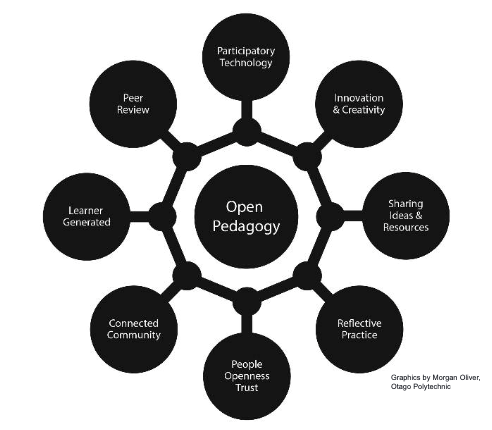

Hegarty (2015) further explores pedagogical aspects of openness in education, and develops a model for using open educational resources to promote openness more broadly. Hegarty describes an “arc-of-life” approach to learning as “a seamless process that occurs throughout life when participants engage in open and collaborative networks, communities, and openly shared repositories of information in a structured way to create their own culture of learning” (p. 3). In this approach, the walls between the institution and the world outside are softened, and learning happens socially within communities and networks.

Figure 2. Eight Attributes of Open Pedagogy

Figure 2. Eight Attributes of Open Pedagogy Note. From “Eight Attributes of Open Pedagogy” by B. Hegarty, 2015, based on G. Conole, 2013.

Figure 2. Eight Attributes of Open Pedagogy Note. From “Eight Attributes of Open Pedagogy” by B. Hegarty, 2015, based on G. Conole, 2013.

Hegarty introduces eight attributes of open pedagogy and explains their main features as follows:

- Participatory technologies: use for interacting via Web 2.0, social networks and mobile apps

- People, openness trust: develop trust, confidence and openness for working with others

- Innovation and creativity: encourage spontaneous innovation and creativity

- Sharing ideas & resources: share ideas and resources freely to disseminate knowledge

- Connected community” participate in a connected community of professionals

- Learner generated” facilitate learners’ contributions to OER

- Reflective practice: engage in opportunities for reflective practice

- Peer review: contribute to open critique of others’ scholarship (Hegarty, 2015).

Again, in line with Cronin’s findings, open pedagogy as an aspect of open educational practices requires of teachers and students a range of technological tools as well as an orientation towards community and sharing. In terms of learners’ contributions to OER, the intent is to create meaningful or “authentic” assignments that have value not only in meeting course requirements and obtaining a grade for credit, but also that can last beyond and outside the course and thus have a more lasting value for both learners and others.

It should be evident by now that there a many elements of open educational practices and they all are interlinked in some way. OER aren’t possible without open licensing, and aren’t meaningful unless incorporated into a culture of sharing and community, requiring social networks and technologies, and so forth. It is at least partly for this reason that notions of openness in education continue to evolve and group into different categories, but once the basic concepts are understood the pieces, however they are contextualized, start to make sense.

Hegarty, B. (2015, July–August). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 3-13. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/Ed_Tech_Hegarty_2015_article_attributes_of_open_pedagogy.pdf

From OER to Open Educational Practices

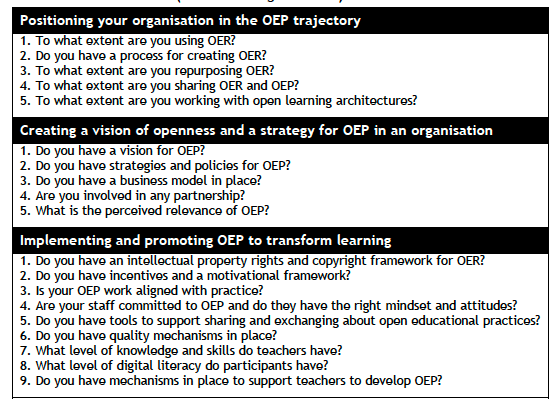

Ehlers (2011) takes a somewhat different approach, focusing on barriers to adoption and use of OER and OEP, not only at the faculty level but also looking at organizational and environmental issues that impact them.

Implementation of OER is broken down into phases, beginning with open content in general and creating OER as opposed to further uptake involving using and reusing them, “…especially with the aim of improving learning and innovating educational scenarios” (Ehlers, 2011, p. 3). The second phase is moving towards Ehler’s definition of OEP, i.e. as noted above improving teaching and learning with the use of OER. This phase has a larger institutional-level implication, in that it is about: “changing the traditional educational paradigm of many unknowledgeable students and a few knowledgeable teachers to a paradigm in which knowledge is co-created and facilitated through mutual interaction and reflection [and] strives to understand that OER has to contribute to institutions’ value chain” (Ehlers, 2011, p. 4). Viewing the adoption of OER and OEP is then viewed as part of an institution’s educational approach and by implication involves strategic-level decision making in supporting and promoting the types of institutional change required to implement OER and OEP across the institution: “They address the whole OER governance community: policy makers, managers/administrators of organisations, educational professionals, and learners (Ehlers, 2011, p. 4).

Ehlers places OEP within matrices that measure usage from low to medium to high levels, and the underlying types of learning architecture as well as the expanding involvement of others as OEP adoption continues to grow and diffuse within an institution. Ehler’s framework for supporting OEP includes an organization model for indicating the maturity level of OEP participation within an institution, in terms of a shift from OER to OEP. Stated as a series of questions, the framework can be used to study your own or other educational institutions to assess the extent of OEP transition as well as, potentially, to develop a road map for improvement, if desired, in this area (see Figure 3).

Table 1. The OEP Model (Version for Organizations)

Table 1. The OEP Model (Version for Organizations). Note. From “The OEP Model” by U. D. Ehlers, 2011, Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning. (http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64/46)

Table 1. The OEP Model (Version for Organizations). Note. From “The OEP Model” by U. D. Ehlers, 2011, Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning. (http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64/46)

Ehlers notes that free content by itself isn’t sufficient to transform teaching and learning at the institutional level. Rather, it needs to be accompanied with changed learning models

Ehlers, U. D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1-10. http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64/46

Open Content and Open Educational Resources

An issue of ongoing concern, and today more than ever, is the cost of education. For K–12 schooling, the costs are mainly borne by governments and thereby taxpayers, and beyond that students pay for their schooling through a combination of government subsidies and student tuition fees (i.e., higher education).

A large cost item in education is in textbooks, regardless of who is paying for them. Increasingly there is a movement to create open textbooks, defined this way by BCcampus:

An open textbook is a textbook licensed under an open copyright license and made available online to be freely used by students, teachers, and members of the public. They are available for free as online versions, and as low-cost printed versions, should students or faculty opt for these. (BCcampus, n.d., n.p.)

Take a few minutes to look around the BCcampus website, and you will see a large list of open textbooks that are free for faculty to simply take and use as they will at no cost. Open textbooks are a recent development in an earlier movement that started over the past few decades to promote open educational resources (OER). OER are defined by UNESCO in their 2012 Paris OER Declaration as follows:

Open Educational Resources (OER) are teaching, learning and research materials in any medium – digital or otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions. (UNESCO, 2012)

Thompson Rivers University library has a web section on OER which includes open textbooks, open courseware, and open images, videos, and audio. These resources all use open licenses that permit various forms of free use, according to the conditions of the licences (mostly Creative Commons, as discussed earlier).

The concept of OER has similarities to earlier views of openness as it relates to free and open-source software (FOSS), as discussed earlier. While open textbooks and some OER have been shown to reduce costs in education, another benefit has been the ability to use learning materials in different ways from usual. For instance, many OER have potential for both faculty and students to re-use the content in different ways, as will be discussed next in the “5 Rs” of openness in OER.

The “5 Rs” model itself is an OER with an open licence that permits free use as prescribed by the license. The author, David Wiley, requests in this OER that the following attribution wording be used: “This material was created by David Wiley (n.d.) and published freely under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license at http://opencontent.org/definition/.”

Defining the “Open” in Open Content

|

Wiley, D. (n.d.). Defining the “open” in open content and open educational resources. http://opencontent.org/definition/

Recognition of Informal Learning, PLAR

Beyond open licensing and trying to keep costs down, educators have for many years considered how to make education more accessible to learners using such methods as distance learning and flexible scheduling. Since the 1960s there has been a proliferation of open universities and other educational institutions, developed with the intention of breaking down barriers to higher education using a variety of open educational practices OEPs.

One of the more noteworthy OEPs involves variations of traditional forms of assigning formal credit for learning. In their study, Harris and Wihak (2018) survey practices involving recognition of non-formal education (RNFE) globally. RNFE takes multiple forms. One form is Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition (PLAR). Another option is assigning formal credit for studies conducted using OER and MOOCs. Designing qualifications frameworks, which are defined standards for learning, can be nationally or otherwise determined and referenced by institutions to assign credit based on the learners’ achievement (Harris & Wihak, 2018, p. 3).

Each of the three forms of RNFE described by the authors has its particular advantages. PLAR has growing credibility with academic institutions, and recognition of studies conducted using OER—such as open courseware and MOOCs—have the advantage of potential scale. Qualification frameworks are growing increasingly common. Nevertheless, recognition and assigning of credit for learning is one of the key elements perceived to be the main form of quality control by educational institutions, and it is a difficult idea to promote unless leaders have a strong vision for access to learning.

This is an important issue given the climbing costs of education and the many non-formal learning opportunities that exist today. As noted by the authors:

It has always been an open question as to whether the relentless formalization of learning and education is desirable, even in an era where credentialing is so prevalent and embedded as to be taken for granted. Revisiting this question after this piece of research suggests that RNFE is desirable especially given the extent to which all parties seem to derive benefit from it. There is ample evidence that the process of recognition, albeit demanding, does have a positive effect on the quality of the NFE, and by association, we hope, on the qualification status of individuals and their access to related social and economic benefits. (2008, p. 16)

Harris, J., & Wihak, C. (2018). The recognition of non-formal education in higher education: Where are we now, and are we learning from experience? International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 33(1). http://ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1058

Assessments

Assignment 3: Discussion Posts and Participation (10%)

Discussion Post 4

Begin by reading the course notes above and then select 2–3 of the resources for deeper reading.

Post a 300-word reflection on the resources you have read more deeply, or alternatively record a 3-minute video or podcast and link it into the discussion forum by Thursday of week 7. This reflection should cover the following points:

- Brief summary of the resources

- One thing that stands out for you in each one of them

- How you would fit this in your own practice

Once you have posted, review posts from others and offer insights or questions as appropriate.

Final Project: Major Project Paper (50%)

Final Project Draft

At this point you should be working on a first draft of your major project paper. This first draft is worth 15% of your course grade, and the final submission of your Final Project is worth 35%. This is a mandatory course assessment.

You are asked to submit a rough outline and draft of your paper. The outline should include the main headings and sub headings, with early draft content perhaps in bullet points and brief descriptions of each section where there are still gaps, along with your annotated bibliography. You will receive feedback from your Open Learning Faculty Member.

Post your draft to the Final Project: First Draft dropbox in Moodle and, if you want, as a post on your blog.

Summary Unit 3

In this unit we have explored some examples of what open educational practices might look like. They potentially have wide-ranging implications in the cost of education, the way we teach, our pedagogical understandings and the technologies we use, how we implement technologies, and how we adapt and localize resources for our own contexts. Further, they open up possibilities for increased student engagement in learning.

This is a good time to make sure you are on schedule with your team planning for the discussion and presentation, and your Final Project. Keep up your participation in commenting on others’ discussions.

References

BCcampus. (n.d.). Open textbooks. https://open.bccampus.ca/open-textbook-101/

Blomgren, C. & Roberts, V. (2017). Benefits of OER for K–12 learning [Podcast]. Athabasca University. http://bolt.athabascau.ca/index.php/podcast/benefits-of-oer-for-k-12-learning/

Cavanaugh, C. S., Barbour, M. K., & Clark, T. (2009). Research and practice in K–12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i1.607

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Ehlers, U. D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1-10. http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64/46

Harris, J., & Wihak, C. (2018). The recognition of non-formal education in higher education: Where are we now, and are we learning from experience? International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 33(1). http://ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1058

Hegarty, B. (2015, July–August). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 3-13. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/Ed_Tech_Hegarty_2015_article_attributes_of_open_pedagogy.pdf

Wiley, D. (n.d.). Defining the “open” in open content and open educational resources. http://opencontent.org/definition/

UNESCO. (2012, June 20–22). 2012 OER declaration. UNESDOC. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246687

Lakhan, S. E., & Jhunjhunwala, K. (2008). Open source software in education. Educause Quarterly, 31(2), 32–40. https://er.educause.edu/~/media/files/article-downloads/eqm0824.pdf

Cronin, C., & MacLaren, I. (2018). Conceptualising OEP: A review of theoretical and empirical literature in open educational practices. Open Praxis, 10(2), 127–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.825

Mishra, S. (2017). Open educational resources: removing barriers from within. Distance Education, 38(3), 369–380. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01587919.2017.1369350?needAccess=true

Lakhan, S. E., & Jhunjhunwala, K. (2008). Open source software in education. Educause Quarterly, 31(2), 32–40. https://er.educause.edu/~/media/files/article-downloads/eqm0824.pdf