Topics

On This Page

What are the implications in general for teaching and learning with the use of digital technologies and environments? What are some of the ways in which technologies open up new avenues for teaching and learning and how do we ensure these are done well? The readings in this section explore a few lines of research and practice in this area. The areas covered include teaching and using technologies in a way that promote collaboration and networking among students, opening up more constructivist learning approaches; looking at what types of interactions can best build communities of learning and inquiry in online environments; adopting critical pedagogies that encourage deeper and more critical thinking and understanding of the social injustices that are all too often replicated in our existing educational practices; implementing emerging web technologies in the workplace setting; and the more recent phenomenon of free open courses such as massive open online courses (MOOCs)

Resources

Collaboration / Networked Learning

Connected Learning Alliance. (2013). Professor Alec Couros: “The connected teacher” [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/46442363

Pedagogical Theory(ies)

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 80-97. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/890/1663

Critical Pedagogy and Participatory Practices

Caruthers, L., & Friend, J. (2014). Critical pedagogy in online environments as thirdspace: A narrative analysis of voices of candidates in educational preparatory programs. Educational Studies, 50(1), 8-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2013.866953

Workplace Learning

Caruso, S. J. (2018). Toward understanding the role of Web 2.0 technology in self-directed learning and job performance. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 11(3), 89-98. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184612.pdf

Teaching / Learning in Online or Blended Learning Environments

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. (2018). Tracking online learning in Canadian universities and colleges. https://onlinelearningsurveycanada.ca/publications-2018/

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Chapters 1 & 2. In, Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Athabasca University Press. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.tru.ca/lib/trulibrary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4837975

MOOCs

Daniel, J. (2012, December 13). Making sense of MOOCs: Musings in a maze of myth, paradox and possibility. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2012(3). https://jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-18/

Course Notes

Begin by reading the course notes, and then select 2–3 of the resources for deeper reading.

Collaboration / Networked Learning

Couros (2013) looks at the role of networking in social learning and describes it as an essential concept for educators today. He reviews the different types of social networking tools available to teachers and educators, and how they mediate connections between individuals in networks.

The question that arises out of his discussion is what endures over the longer term? While tools may come and go, the connections and relationships built in networks make a much longer-lasting outcome. It is the building of these connections that is seen as key in networked or connected learning.

Networks can themselves be used to build connections by following those who provide further information about top educators or others to follow, for example. His reference to Digital Storytelling (DS106) refers to a community of people who have built a network around the project challenges available on this site, which started off as an open online course (Digital Storytelling 106) at the University of Mary Washington. The network rapidly grew and became a place where anyone could use and take advantage of the many creative assignments and challenges available on the site. Over time it became almost entirely self-managing with little involvement of instructors.

Couros describes examples of how students can pursue questions by researching and sharing or telling about what they can learn, i.e. “making learning visible” (Connected Learning Alliance, 2013) and helping others to learn by sharing their own learning processes along with the results of their learning.

Connected Learning Alliance. (2013). Professor Alec Couros: “The connected teacher” [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/46442363

Pedagogical Theory(ies)

In their classic article, Anderson and Dron (2011) look at pedagogical approaches in distance education in terms of multiple generations. Generations in this context refers to different eras of time—not in the sense of Millennials or Generation X, but rather in terms of dominant pedagogical theories and ensuing educational practices.

As a sociotechnical development, distance education emanates from a worldview that “defines its epistemological roots, development models, and technologies utilized, even as the application of this worldview evolves in new eras” (Anderson & Dron, 2011, n.p.). These are important concepts in building an understanding of distance education and, for that matter, a relationship between culture and technology (e.g., technology and methods, in this case, used in distance education).

The term “sociotechnical” is used by Anderson and Dron to encapsulate the idea that technology doesn’t exist and operate on purely technical terms. For instance, when a technology is incorporated in education, it doesn’t just work by itself but rather in concert with the goals of the users, the reasons for its implementation, the current understanding of what the technology can and cannot do, infrastructure available to support it, and other such elements. In other words, there is much complexity around technical systems used in education.

In distance education, technology is used to mediate communication and connection between learners, instructors, and resources. Anderson and Dron describe three generations of pedagogy that interact with views of technology and how it’s being used in education: cognitivist-behaviourist, social-constructivist, and connectivist. In each of these paradigms the authors look at the roles of cognitive, social, and teaching presence in the pedagogical approaches; i.e., how each of these three areas are present and used within the distance education system and teaching and learning environment at play.

These three elements are derived from the “community of inquiry” framework developed by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000). As they describe it:

Although the prime actors in all three generations remain the same—teacher, student, and content—the development of relationships among these three increases from the critical role of student–student interaction in constructivism to the student–content interrelationship celebrated in connectivist pedagogies, with their focus on persistent networks and user-generated content. (Anderson & Dron, 2011, n.p.)

Figure 1. Community of Inquiry Framework

While there are different views of these and other possible generations of pedagogy or worldviews on teaching, learning, and technology, the important thing is to understand the complex relationships between pedagogical approaches, technologies, and types of presence and interactions among them.

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 80-97. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/890/1663

Critical Pedagogy and Participatory Practices

From another perspective, Caruthers and Friend (2014) explore views and uses of technology in relation to issues of social justice that are framed within the context of exploration of learners’ own cultures and backgrounds. Rather than viewing online spaces as neutral, they may be safe spaces where deeper explorations among learners can take place, as well as the development of critical views, but also where power relations can suppress the diversity of voices and ideas. As they put it, their interest “lies in using the online environment for critical dialogue and practices around issues of race, ethnicity, gender and other differences which require teachers and leaders using their voices to examine current regimes of knowledge” (Caruthers & Friend, 2014, p. 12). By “regimes of knowledge” the authors are referring to “hegemonic narratives” that can often control and hold sway in the classroom, suppressing open discussion and critique of education and its role in culture, including the very education that is taking place within teacher development learning environments:

In other words, people have the power to resist hegemonic narratives that control their lives; critiquing the dominant curriculum, the instrumental use of knowledge, and its discourses and discursive practices. Such a task will require that educators look inside and outside themselves to adopt a critical praxis—one that critiques the role that schools play in our political and cultural life. (Caruthers & Friend, 2014, p. 13)

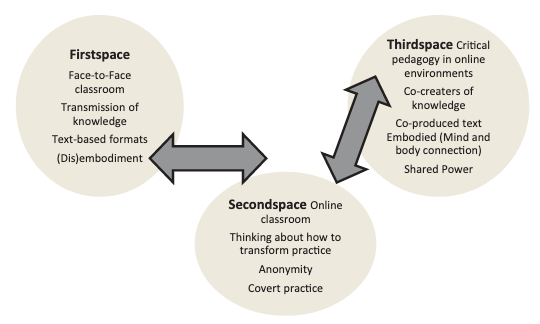

Against this background, Caruthers and Friend present the concept of “Thirdspace,” referring to spaces where learners have safe room to explore and develop critical understandings of teaching and learning in society, or “critical pedagogy” that encourages alternative thinking to dominant narratives: “In Thirdspace, the shift occurs as a result of instructors becoming more aware of what the learner brings to the process, and the constructivist nature of learning that promotes shared power between instructors and learners” (Caruthers & Friend, 2014, p. 14).

Why “Thirdspace”? The first space is described as the face-to-face classroom, where knowledge tends to be delivered using a transmission (didactic or lecture) method. The second is the online classroom, which is different from physical space but tends to be anonymous and disembodied. The Thirdspace is where “as teachers and learners become aware of their own embodiment in online environments, they learn that knowing, acting, and being are integral parts of who we are” (Caruthers & Friend, 2014, p. 16) as part of exploring and discussing such aspects as culture, identity, and voice. Thirdspace is portrayed in a model with some visual similarities, but otherwise many differences, to the community of inquiry model.

Figure 2. The Relationship between Instructional Environment and Critical Pedagogy

Figure 2. The Relationship between Instructional Environment and Critical Pedagogy From Loyce Caruthers & Jennifer Friend (2014) “Critical Pedagogy in Online Environments as Thirdspace: A Narrative Analysis of Voices of Candidates in Educational Preparatory Programs”, Figure 1, The relationship between instructional environment and critical pedagogy, Educational Studies, 50:1, 8-35, DOI: 10.1080/00131946.2013.866953, reprinted by permission of American Educational Studies Association, http://www.educationalstudies.org/

Figure 2. The Relationship between Instructional Environment and Critical Pedagogy From Loyce Caruthers & Jennifer Friend (2014) “Critical Pedagogy in Online Environments as Thirdspace: A Narrative Analysis of Voices of Candidates in Educational Preparatory Programs”, Figure 1, The relationship between instructional environment and critical pedagogy, Educational Studies, 50:1, 8-35, DOI: 10.1080/00131946.2013.866953, reprinted by permission of American Educational Studies Association, http://www.educationalstudies.org/

The Thirdspace is devoted to the idea of transformative learning. Citing Giroux and Giroux (2006), the authors note that Thirdspace is about “linking learning to social change, education to democracy, and knowledge to acts of intervention in public life” (Caruthers & Friend, 2014, p. 31).

Many educators end up in roles outside of public school and higher education institutions. The approaches to learning in these settings are typically vastly different from the Thirdspace understanding; although some organizations are rethinking their approaches knowing that narrowly-conceived training programs may not produce the creative and innovative employees they claim to want. Roles in non-public school and higher education may include not-for-profits, government agencies, Indigenous communities, health care, and for-profit industry. These environments tend to have more clearly spelled-out competency requirements to meet organizational goals. So how can technology be incorporated in these environments and to what end?

Access the Caruthers and Friend reading via TRU Library:

Caruthers, L., & Friend, J. (2014). Critical pedagogy in online environments as thirdspace: A narrative analysis of voices of candidates in educational preparatory programs. Educational Studies, 50(1), 8-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2013.866953

Workplace Learning

Within this context, Caruso looks at Web 2.0 (Techopedia, 2017) technology and its connection to learning and performance in the workplace. Web 2.0 marks the transition in the way people interacted with the Internet in its early days with a shift from static websites to what is sometimes called the “read-write Web.” In other words, the Web became more than something that is just read and consumed; it is also used for adding and modifying content, collaboration and creative engagement. Web 2.0 takes the form of such tools as social media, Web-based communities, blogs, and such sharing sites as YouTube and SoundCloud.

Caruso (2018) explores how self-directed learning can be used as an approach to performance support within the work environment, with Web 2.0 as a key resource. In self-directed learning, learners take increased responsibility for finding the resources that will help them learn what they need to know or do to improve performance. Within the workplace setting, in comparison to the spaces provided in public education, there is often an expectation that management makes decisions about organizational goals, evaluates the performance levels of employees against those goals, and then communicates to employees their achievement of goals and where performance is lacking. In contrast to traditional organizational training methods, Web 2.0 tools provide more options for learning as a continuous rather the periodic event; to enable this “organizations should provide adequate time, opportunities, resources, and incentives to develop competencies in using Web 2.0 technologies to solve problems and perform tasks” (Caruso, 2018, p. 96). This type of fluidity is seen as helping to create a more skilled and knowledgeable workforce.

Caruso, S. J. (2018). Toward understanding the role of Web 2.0 technology in self-directed learning and job performance. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 11(3), 89-98. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184612.pdf

Teaching and Learning in Online or Blended Learning Environments

Over the past few years, the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association has conducted an annual national survey to learn more about online learning in Canadian Universities and .

With a high survey response rate, the findings have been put into an infographic format that can be accessed online (eCampusOntario, 2018); a reduced version is provided below.

Among the findings:

- 8% of all course registrations in Canada are fully online

- 74% of institutions surveyed anticipate an increase in course registrations over the following year

- Of students in Canada, one fifth take one online course at minimum

- Over half of those students are engaged in open educational resources and open textbooks

- 68% of institutions have increased attention to online learning in their strategic plans

- Access is a key element of online learning, together with growing continuing education and recruitment from outside the traditional pools

- 78% of perceptions of quality of online courses in comparison to traditional courses for both blended and online learning is the same or in some cases superior

- Among the largest barriers to more adoption of online learning are:

- Faculty time requirements

- The need for skills and development in online learning

- Lack of acceptance at the faculty level

A key originating member of the survey team, Tony Bates reflects in a blog post (2019) on some of the meanings of these numbers and results. Among his main points:

- Canada is much lower than the US in uptake of online learning; however, a big proportion of this uptake may be from the existence of large for-profit institutions, such as the University of Phoenix, and not-for-profit private institutions. These and other large online universities account for a large proportion of enrolments.

- Quality is generally seen as high.

- Some of the challenges are resistance by faculty, who generally do not receive the training required to successfully develop and deliver online learning. This training is not just about use of technology, but also pedagogical methods for teaching and learning in online environments. As noted by Bates:

Faculty training becomes even more important as faculty move into blended learning. Far too often I am seeing classroom lectures merely transferred to video delivery with very little adaptation, and little understanding of the needs of distance learners. It is not just a question of what – introducing pedagogy and different teaching approaches – but how: how to scale up the training when eventually all instructors will be using some form of blended learning (Bates, 2019, n.p.).

From an institutional perspective, in almost any context, these findings can be taken seriously if online learning is to be used in any sector, whether higher education or K–12, or other private or public sector learning:

This also relates to my last point: we need to move beyond seeing online learning as just improving access (as important as that is) to seeing it as a key tool for developing 21st century skills, especially digital skills, independent learning, critical thinking. and communication. This requires combining online learning with new pedagogical approaches: a challenge indeed. (Bates, 2019, n.p.)

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. (2018). Tracking online learning in Canadian universities and colleges. https://onlinelearningsurveycanada.ca/publications-2018/

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Chapters 1 & 2. In, Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Athabasca University Press. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.tru.ca/lib/trulibrary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4837975

MOOCs

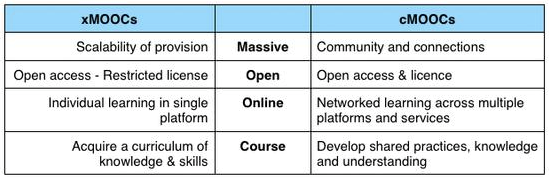

In the context of open education and online learning, over the past decade and some years there has been a growth in the phenomenon of MOOCs. The term refers to massive open online courses, which have a contested history but are generally seen as having come to prominence in Canada in 2008 with the delivery of “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge,” a course offered by the University of Manitoba to registered students and also opened up to over 2,000 others for free. The course used a variety of social media and collaboration tools—ranging from blogs and Moodle, to virtual meetings in Second Life—with many of these nodes connected through RSS (web syndication) to enable tracking different threads and developments in this decentralized learning environment. This and later versions of MOOCs were known as cMOOCs or “connectivist” MOOCs, as compared with the later development of what became termed xMOOCs at Stanford, MIT, and other institutions and with the growth of Coursera, Udacity, FutureLearn, and other such MOOCs. Differences between cMOOCs and xMOOCs are portrayed in the following table.

Table 1. MOOC Typologies, analyses and gives an overview of the different forms of MOOCs in terms of massive, open, online, and course

Table 1. Tabulation of the Significant Differences between xMOOC and cMOOC Note. From “Beyond MOOCs” by L. Yuan, S. Powell, & B. Olivier, 2014. (http://publications.cetis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Beyond-MOOCs-Sustainable-Online-Learning-in-Institutions.pdf) CC BY 4.0

Table 1. Tabulation of the Significant Differences between xMOOC and cMOOC Note. From “Beyond MOOCs” by L. Yuan, S. Powell, & B. Olivier, 2014. (http://publications.cetis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Beyond-MOOCs-Sustainable-Online-Learning-in-Institutions.pdf) CC BY 4.0

Wikipedia’s entry for massive open online course (2020) provides a detailed and comprehensive history of MOOCs. In his analysis, Daniel (2012) describes the education philosopher Ivan Illich’s (1971) views on how education should function in society. Early MOOCs exemplify, in Daniel’s view, “Ivan Illich’s injunction that an educational system should ‘provide all who want to learn with access to available resources at any time in their lives; empower all who want to share what they know to find those who want to learn it from them; and, finally furnish all who want to present an issue to the public with the opportunity to make their challenge known’” (Illich, 1971, as cited in Wikipedia, 2019).

The idea of early MOOCs was grounded in a larger vision of social and pedagogical benefits derived from using the Web as a place of flexible and open learning, rather than the usual closed locations of the classroom and the LMS. However, in 2012 a bandwagon of new, different offerings—xMOOCs—came into play from Stanford and then other universities. These developments became more about affiliating with “status” universities and the perception of money to be made, as opposed to the original intention of early cMOOCs.

Early results were strongly criticized, since the new xMOOCs were striking out in substantially different directions with many outlandish promises, such as replacing most universities in the near future, generating massive revenues, and the idea that MOOCs being offered by leading universities would somehow guarantee excellent learning experiences, which in the end did not happen. Apart from these developments, Daniel sees potential in such possibilities as a new focus on teaching and pedagogy.

Daniel, J. (2012, December 13). Making sense of MOOCs: Musings in a maze of myth, paradox and possibility. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2012(3). https://jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-18/

Assessments

Assignment 1: ePortfolio and Blog Posts (20%)

Blog Post 4

Record and publish a 4–5 minute reflection using video, audio, or other media tools to describe key elements of what you have gained from the readings in Unit 4. Comment on at least two resources. Be as creative as you wish, but respond to, at minimum, the following questions:

- Which resource(s) are you reflecting on? (Minimum of two.)

- What is the main position, hypothesis, argument, or finding of the resource(s)?

- What do you agree with or disagree with, and why?

- How does it/do they apply to your own context or a setting you are familiar with?

- What recommendations would you make for your organization in relation to what you have learned?

If you decide to record a video, you can host it on YouTube or Vimeo, and use SoundCloud or Audacity for audio recordings. Feel free to share ideas for recording and hosting tools with class members or consult your Open Learning Faculty Member for specific applications.

Summary

Unit 4 has provided an introduction into some of the directions teaching and learning can take with the use of technology and some creative pedagogical approaches. As these approaches continue to grow in education as new and enhanced forms of educational practice, they must nonetheless still be implemented in consideration of the other areas discussed in the course such as ethics, social justice, access and so forth. These are all part of a larger picture, and it is all too easy to get caught up in one particular technology and its seemingly attractive benefits without taking a step back and ensuring it is a good fit and that it meets an existing or new pedagogical need.

References

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 80-97. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/890/1663

Bates, T. (2019, January 27). Some reflections on the results of the 2018 national survey of online learning. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources. https://www.tonybates.ca/2019/01/27/some-reflections-on-the-results-of-the-2018-national-survey-of-online-learning/

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. (2018). Tracking online learning in Canadian universities and colleges. https://onlinelearningsurveycanada.ca/

Caruso, S. J. (2018). Toward understanding the role of Web 2.0 technology in self-directed learning and job performance. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 11(3), 89-98. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184612.pdf

Caruthers, L., & Friend, J. (2014). Critical pedagogy in online environments as thirdspace: A narrative analysis of voices of candidates in educational preparatory programs. Educational Studies, 50(1), 8-35.

Connected Learning Alliance. (2013). Professor Alec Couros: “The connected teacher” [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/46442363

Daniel, J. (2012). Making sense of MOOCs: Musings in a maze of myth, paradox and possibility. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2012(3). https://jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-18/

Deschooling society. (2019, December 21). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deschooling_Society

eCampusOntario. (2018, November). The rise of online learning in Canadian universities and colleges [Infographic]. https://www.ecampusontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Infographic-TESS-ENG-WEB.pdf

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/

Massive open online course. (2020, February 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massive_open_online_course

Techopedia. (2017, April 26). Web 2.0. https://www.techopedia.com/definition/4922/web-20

Yuan, L., Powell, S., & Olivier, B. (2014). Beyond MOOCs: Sustainable online learning in institutions. Cetis Publications. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massive_open_online_course#/media/File:Li_Powell_Olivier_2014_xMOOC_cMOOC_significant_differences_table.jpg